30 Forest Minutes for De Beauvoir Jazz Festival Goers 🎷🚲

At De Beauvoir Jazz Festival this weekend? Forest has your ride covered. We're giving all festival goers 30 minutes of free riding time!

Whether you're cruising in for the first set, exploring the Forest checkpoints on the cycling tour, or heading home after a soulful evening, just hope on a Forest bike and enjoy the journey on us!

LEARN MORE | Forest Checkpoints

A - Collins Music Hall (converted use), Islington Green

Located at 10–11 Islington Green, Collins Music Hall opened in 1863 behind a pub, named after Irish entertainer Sam Collins. It became a cornerstone of Victorian entertainment and famously “never closed,” remaining open through the Blitz and only pausing briefly in 1898 to install electric lighting. The hall was destroyed by fire in 1958, leaving only its facade, which still stands today. Redeveloped in 2008, the site now houses a residential and retail complex, but its legacy endures as a vital part of Islington’s cultural and working-class history.

B - Union Chapel, Compton Terrace

Completed in 1877, Union Chapel is a Grade I-listed Gothic Revival church built as part of the Nonconformist movement, promoting religious freedom and social justice. It remains both an active church and a renowned music venue, known for its stunning acoustics and intimate atmosphere. Since the 1990s, it has become a key destination for acoustic and jazz performances, offering a sacred setting that enhances emotional expression. Beyond music, the chapel continues its legacy of social outreach, serving the community with crisis support and homelessness services – a true reflection of Islington’s progressive spirit.

C - The Rhythm Club, 100 Holloway Road

Founded in 1942 as a record appreciation society, the Islington Rhythm Club quickly became one of London’s key post-war jazz venues. Starting with discussions and recordings, it evolved into a live performance space after WWII, playing a vital role in Britain’s jazz transition from swing to bebop. Its democratic roots encouraged audience engagement and musical experimentation, hosting both revivalists like George Webb and modernists like Humphrey Lyttelton. Later known as T&C2 and now The Garage, the venue helped establish jazz as an intellectual and accessible art form in Britain.

D - Four Aces Club (demolished), 12 Dalston Lane

Opened in 1966 by Jamaican-born Newton Dunbar, The Four Aces was one of London’s first venues dedicated to showcasing Black musical talent. Originally a jazz and blues club, it soon became a vital hub for reggae, soul, and Caribbean-influenced jazz. From 1966 to 1975, it offered a rare platform for artists like Joe Harriott, Shake Keane, and Harold McNair, who were often excluded from mainstream venues. More than a music venue, it was a cultural force that challenged industry norms and fostered hybrid styles. Despite efforts to save it, the club was demolished in 2007 during Dalston’s regeneration.

E - Café Oto

Since opening in 2008, Café Oto has become a cornerstone of London’s experimental music scene. Housed in a converted Victorian railway arch, its raw, intimate setting hosts cutting-edge performances at the intersection of jazz, improvisation, and sound art. Founded by Keiko Mukaide and Otto Willberg, the venue treats jazz as a living art form, reinterpreting tradition while championing innovation. With tributes to artists like Ahmed Abdul-Malik and Derek Bailey, and a community-driven spirit, Café Oto is both a performance space and creative hub at the heart of Dalston.

F - Vortex Jazz

Founded in the early 1990s by former taxi driver David Mossman, the Vortex Jazz Club found its permanent home in Dalston’s Gillett Square in 2005. Housed in a former industrial site, the venue played a key role in the area’s cultural revival. From grassroots beginnings, it has grown into one of the world’s top jazz venues, recognised by Downbeat magazine. The Vortex champions a wide range of styles, from traditional to avant-garde, and hosts Mopomosi, the UK’s longest-running improv night. Run largely by volunteers, it remains a vital part of London’s jazz and arts community.

G -Stamford Works Studio (converted use), Gillett Square

Opened in 1962 in a converted Victorian factory, Stamford Works played a vital role in British jazz recording through the 1960s and ’70s. Built to support independent jazz musicians excluded by major labels, the studio offered top-quality acoustics and multi-track capabilities at affordable rates. It hosted landmark sessions by artists like Stan Tracey, Bobby Wellins, and Ian Carr, helping elevate British jazz to international standards. As one of Dalston’s earliest creative spaces, Stamford Works laid the groundwork for the area’s cultural transformation and directly paved the way for venues like the Vortex Jazz Club.

H - Centerprise Jazz Basement (converted use, no entry)

From 1971 to 1992, Centerprise combined radical bookshop, community centre, and jazz venue in one space, rooted in the political and cultural activism of the era. Its basement club became a hub for avant-garde and free jazz, offering an alternative to mainstream venues. Musicians like Evan Parker, John Stevens, and Trevor Watts used the space as a creative lab for improvisation, fostering the growth of British free jazz. With its intimate, informal setting, Centerprise broke down barriers between artist and audience, leaving a lasting mark on the UK’s experimental music scene.

I - EartH (Evolutionary Arts Hackney)

Originally opened in 1936 as the Savoy Cinema, this Art Deco venue was once a glamorous hub for film lovers, seating over 2,700 people. Changing times saw it become the ABC Cinema, then a bingo hall in the 1970s, before falling into disrepair by the ’90s. In 2018, it was reborn as EartH, a multi-arts venue created by the team behind Village Underground. Now a key site for jazz and soul, it has hosted artists like Mulatu Astatke, Sun Ra Arkestra, and Nubya Garcia, and is a regular fixture of the London Jazz Festival.

J - Total Refreshment Centre (converted use, no entry)

Housed in a former 1904 confectionery factory, the Total Refreshment Centre (TRC) became a cornerstone of London’s jazz renaissance before its closure in 2018. Reopened in 2012 through a DIY community effort, the space held nine studios and a raw performance area, attracting artists drawn to its concrete walls and industrial sound. TRC played a crucial role in shaping the "new London jazz scene," nurturing talent like Moses Boyd and Ezra Collective. More than a venue, it was a cultural hub that championed creativity and inclusivity in a rapidly gentrifying East London.

K - Incus Records (est. 1970)

Often cited as Britain’s first independent, musician-run record label, Incus Records was founded in 1970 by Tony Oxley, Michael Walters, Derek Bailey and Evan Parker. Focused on free improvisation, it became a key platform for avant-garde jazz in the UK. Guitarist Derek Bailey, a pioneer of the genre, helped shape its direction and global reputation. His influential book Improvisation: Its Nature and Practice in Music and the accompanying TV series cemented his legacy—and that of Incus—as vital to the history of improvised music.

L - Hackney Empire

Opened in 1901 and designed by Frank Matcham, Hackney Empire has hosted everything from variety theatre to TV broadcasts and bingo. Restored in the 1980s, it became a vital jazz venue thanks to its association with the Jazz Warriors, an all-Black British collective led by Courtney Pine and Gary Crosby. Their landmark 1987 concert, held in solidarity with the Anti-Apartheid movement, cemented the Empire’s role in blending musical innovation with political activism. As a performance hub, it became key to the British jazz revival and a cultural anchor for Hackney’s diverse communities.

For more info about each location, check out the De Beauvoir Jazz Festival website here.

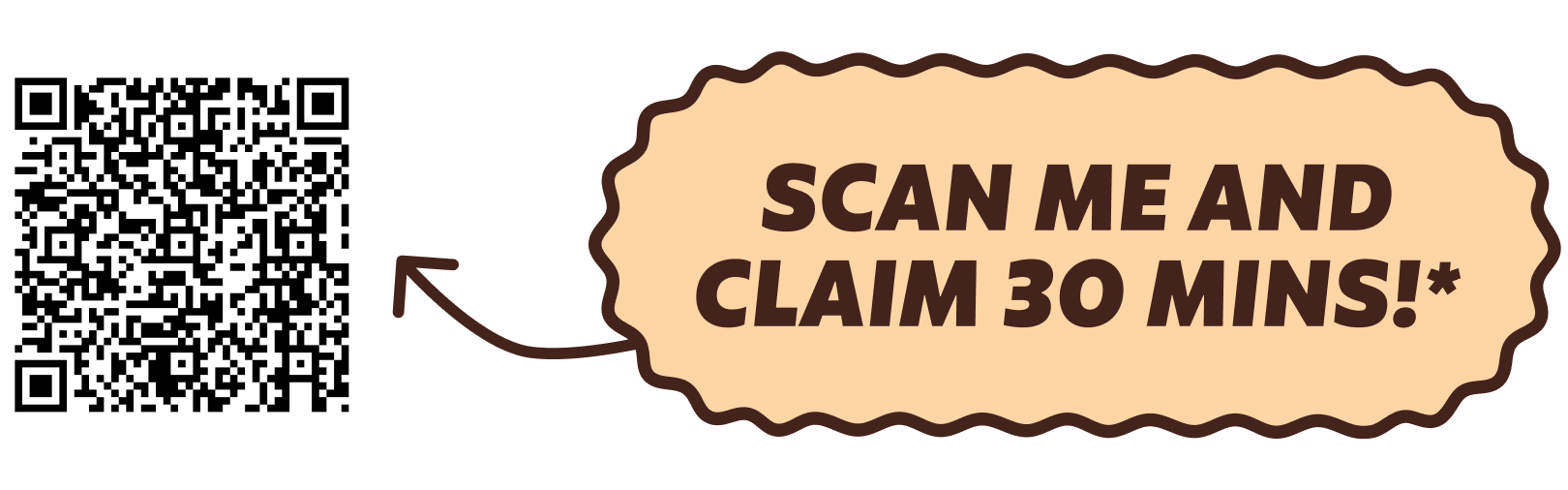

Viewing on desktop? Scan me here with your phone camera to claim minutes!

*Start ride fees apply. Once redeemed, you gave 48 hours to use 30 minute code. Code expires on the 15th of July.